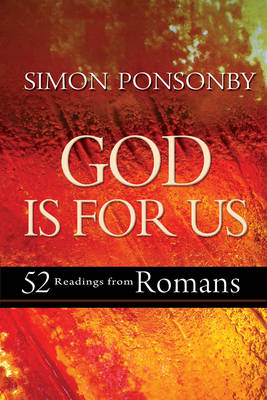

‘God Is With Us’ is a theologically rich book by Simon Ponsonby, guiding you through the theological and historical detail of Paul’s powerhouse letter to the Roman Church.

This is the first chapter of Simon’s book, which he has kindly allowed Vineyard Churches to reproduce free of charge. To read this insightful and brilliantly written book in it’s entirety you can buy it from Vineyard Records UK.

This is the first chapter of Simon’s book, which he has kindly allowed Vineyard Churches to reproduce free of charge. To read this insightful and brilliantly written book in it’s entirety you can buy it from Vineyard Records UK.

We have fifty-two chapters ahead of us. Why is it worth spending so long studying this epistle so closely? When anyone asked that question over the many months of Sundays that I preached on it, my answer was simple: “Because we don’t have any longer.”

As I began this study, a former graduate student, who had attended the distinguished New Testament professor Howard Marshall’s Greek language class at Fuller Theological Seminary, told me that he began his study on Romans with these words: “First, never teach a course on Romans; second, if you have to teach a course on Romans, never try to teach all of Romans.” Why so reluctant?

Romans is massive. It is Paul’s magnum opus, his masterpiece…

Well, intellectually and theologically, Romans is massive. It is Paul’s magnum opus, his masterpiece, and also the longest church epistle in the New Testament. The question of which is the best route to scale such a mountain has entertained the church for centuries – many of its greatest theologians have attempted it. In heaven I suspect there’s a Bible-study group with Origen, Augustine, Aquinas, Wesley, Barth, Lloyd-Jones and many others all debating it.

Let’s consider some introductory questions.

Authorship

Romans begins, “Paul, a servant of Christ Jesus, called to be an apostle…” The letter claims to be from Paul and there is no evidence to suggest otherwise. Despite the tendencies of historical critical theology to not take everything biblical at face value, Paul’s authorship of this epistle has never seriously been in question, and, unlike certain other New Testament epistles, there is no scholarly assertion that it could be pseudonymous. It is true that in 16:22 it states, “I Tertius, who wrote this letter, greet you in the Lord” but most scholars assume that Tertius was the scribe to whom Paul dictated the letter, despite the odd one or two scholarly claims to the contrary.

Most scholars assume that Tertius was the scribe to whom Paul dictated the letter.

Some commentators have questioned whether Romans 16 was part of the original letter at all. Some speculate that that particular chapter, at least, was written by Tertius. But the major reason for suggesting the last chapter has been added on is that the author seems fully acquainted personally with at least twenty-six people in the Roman church, whom he names and to whom he sends personal greetings. It is therefore asked: how could Paul know so many people there if he had not founded or even visited the church? (Paul’s known visits to Rome were made after this letter was written.)

This is not a problem that should cause any serious questioning. Rome was the centre of the empire – an empire in which many moved quite freely for trade. Paul could well have known or met some of those named in other major cities as they were about their trade, before they found themselves in Rome (notably Epaenetus (16:5) who is called “the first convert to Christ in Asia”). We are well aware that all Jews were expelled from Rome some years prior to Paul writing, and some of those named may have been Jewish believers who fled to cities and joined the churches where Paul was ministering. While Paul names twenty-six individuals, he does not claim to know all of them personally: three he says are “relatives”; two “dear friends”; three he calls “fellow workers”; one he “loves in the Lord” and one has been a “mother” to him. It is possible the rest he knew about, had heard of, and as apostle to the Gentiles was daily in prayer for, as he says: “God … is my witness how constantly I remember you in my prayers at all times” (1:9–10). Such constant carrying of them in his heart before God in prayer meant he knew them, loved them, and wanted to greet them – even if he had never met them!

The occasion

In 15:25–26 we read that Paul is shortly to take a trip to Jerusalem, where he will hand over funds raised by the churches in Macedonia and Achaia to assist the struggling saints in Israel (Acts 19:21). Paul says he intends afterwards to go on apostolic mission to Europe, starting in Spain, visiting the Roman church on the way, and hopes they will furnish his mission trip – presumably with prayer support, financial backing, and even colleagues to accompany him.

This would date the writing of the letter sometime between ad 55 and 57.

We may triangulate this statement with two other passages to pinpoint the time and occasion of this letter. In 2 Corinthians 1:16 Paul states that he intends to visit the Corinthian church before going to Judea, collecting their contribution to the gift for the struggling church in Jerusalem (2 Corinthians 8). In Romans 16:1–2 Paul commends Phoebe to them; she is part of the leadership in the church of Cenchreae and is entrusted with carrying this letter to the church in Rome. Cenchreae is a seaport in northern Corinth. So we may deduce that Paul wrote this letter on his visit to Corinth, just before his visit to Rome, at the end of his third missionary journey. This would date the writing of the letter sometime between ad 55 and 57. He was arrested in Jerusalem, and after appealing to Caesar was taken to Rome, placed under house arrest and, we believe, eventually executed around ad 62. Interestingly we have two very early manuscripts with scribal ascriptions saying the letter was written by Paul from Corinth.

The recipients

Chapter 1, verse 7, addresses the letter “To all in Rome who are loved by God and called to be saints”. This is the only letter in Scripture that Paul wrote to a church he didn’t found. There had never been a formal apostolic mission to Rome. The origins of this church – or more accurately a network of house churches in Rome1 – are not presented in Scripture, although we may attempt some reasonable deductions about it. We know there was a large Jewish community in Rome in the early first century ad with upwards of 50,000 members, including many who had been taken there as slaves following Pompey’s subjugation of Palestine in 62 bc. Some made the major pilgrimage to Jerusalem for the sacred Pentecost festival – Acts 2:10 tells us that there were visitors from Rome present on the day of Pentecost. They would have witnessed the Spirit being poured out and heard Peter’s sermon, and we may naturally assume they were among the 3,000 converted that day. If so, these would form the nucleus of the church or churches on their return to Rome. Acts 8:1 informs us of a severe persecution that broke out following Stephen’s stoning in Jerusalem, and the church was scattered; again it is plausible that some of those Christians found their way to Rome and either founded or supported the embryonic church there.

This is the only letter in Scripture that Paul wrote to a church he didn’t found.

An important insight into the origins of the church in Rome is offered by the fourth-century writer Ambrosiater:

It is established that there were Jews living in Rome in the times of the Apostles, and that those Jews who had believed [in Christ] passed on to the Romans the tradition that they ought to profess Christ but keep the law [Torah] … One ought not to condemn the Romans, but to praise their faith, because without seeing any signs or miracles and without seeing any of the apostles, they nevertheless accepted faith in Christ, although according to a Jewish rite.2

This is significant. Jewish believers had passed on the faith to Roman Gentiles, but with a Jewish bent – keeping the law! It’s possible that issues raised by this provoked Paul’s writing of this letter and shaped its particular content. At times Paul is clearly addressing Jewish believers (2:17; 4:1; 7:1) and at other times Gentile believers (11:13), and he probably has Jewish believers in mind in 2:1 – 3:8 and 7:1–6; and is addressing Gentile believers in 9–11. In chapter 14 he appears to be saying to both groups who have been squabbling, “Come on, shake hands, play nice.”

The purpose

As with many letters or emails we might write, there is often more than one motive behind them and more than one message contained within them. I think Paul has several reasons in writing to the Roman church.

This letter serves as a formal introduction to the church and a preparation for his hoped-for coming.

First, as the “apostle to the Gentiles” (Romans 11:13; see also Acts 9:15) it would be appropriate that he should be connected to the church in the capital of the Gentile empire. This letter serves as a formal introduction to the church and a preparation for his hoped-for coming (1:11, 15:29).

Secondly, Paul intends to embark on a fourth mission, up into Spain, and needs to establish a support base for that in Rome. This letter serves to introduce himself and his intention to them for consideration of support (15:24).

Thirdly, Paul wants to commend Phoebe to the Roman church leadership (16:1) and he exhorts them to assist her. We do not know the nature of the assistance she requires, but his letter, delivered by Phoebe’s hand, with so many personal greetings attached to it, would hopefully mean that their hearts and hands would open to her.

Fourthly, Paul states that he has wanted to come and preach the gospel to them but has been hindered from doing so (1:13–15). Unable at this moment to come and preach personally, he may well be dictating something of his gospel, so that at least he will be heard, and his message conveyed, as it is read aloud to the congregations.

Paul is writing to resolve a pastoral tension in the church.

Fifthly, and centrally, Paul is writing to resolve a pastoral tension in the church, precipitated by theological disagreement between Gentile and Jewish camps, which he has caught wind of (11:17–25; 12:16; 14:3). This is the work of one exercising his ministry of reconciliation (2 Corinthians 5:18).

As noted above, the church in Rome almost certainly began among the Jewish community and took on a Jewish flavour and Jewish leadership. But in ad 49 the Jews were expelled by Emperor Claudius (Acts 18:2) over strife about someone the writer Suetonius later calls “Chrestus” – that is, “Christus”. It’s fair to assume that, when the Jewish Christians were expelled, Gentile leadership modified the Jewishness of the church theology and worship. When the Jews were welcomed back to Rome in the mid-fifties, the Jewish church leaders and members returned, and tensions arose over such issues as the place of Jews in God’s economy (Romans 9–11), the role of the law (Romans 4–7), Jewish food regulations, sabbath days, and so on (Romans 14). Paul is thus seeking to bring rapprochement between two ethnic groups by means of different expressions of theology and spirituality. The church has struggled ever since to hold together the Jewish roots of the Christian faith in a predominantly Gentile culture with Gentile church leadership.

Lastly, Paul would shortly be a prisoner, under house arrest in Rome. Though he did not foresee this, in God’s economy making contact with the church would be pragmatically beneficial. Under house arrest in Rome they could tend to his needs and engage in mutual encouragement (Acts 28:15f; 30f).

The major themes

The distinguished church historian, Philip Schaff, wrote that Romans is the most remarkable product of the most remarkable man. It is his heart. It contains his theology, theoretical and practical, by which he lived and died.3

Romans is the most remarkable product of the most remarkable man.

This tends to have been the general consensus, certainly among evangelicals and Protestants for centuries – that this is the fullest, clearest expression of Paul’s theology; his gospel, his systematic doctrine. The Reformer Philipp Melancthon called it “a compendium of Christian doctrine”.4 But are these views right?

While the letter is skilfully and carefully crafted, that this is Paul’s systematic theology seems unlikely – there are huge omissions in this letter which he explicates elsewhere. Noticeably it lacks any clear doctrine of the church as we see it in Ephesians 2–4; it lacks any expanded Christological statements as we see in Colossians 1:15–20 and Philippians 2:6–11; it makes little mention of eschatology as we find in 1 Thessalonians 4:13 – 5:11; 2 Thessalonians 2:1–12; and it has little to say on personal ethics, as we find in Ephesians 5–6. Its relative paucity in the areas of Christology, ecclesiology, and eschatology would suggest it is not an attempt at systematic theology. Furthermore, its particular and lengthy emphases on matters pertaining to the Jews and the Jewishness of Christianity suggest that it is dealing with a context-specific issue, although one of universal importance to the church. At times it appears almost as an apologetic for the Jewishness of the church; at other times a lengthy apologetic for the sovereignty of God.

For years scholars have debated what is at the centre or “heart” of Paul’s thought. New Testament professor C. K. Barrett goes so far as to say that one would not be wrong in seeing the verses 1:16–17 as “a summary of Paul’s theology as a whole”.5 But that view is not one that is shared by most other theologians. It is surely significant that great theologians and movements that have focused on Romans have all emphasized different themes and portions of Romans as being at the centre. For Augustine it was Romans 5 and original sin; for Martin Luther it was Romans 3–4 and justification by faith; for John Calvin it was Chapter 9 and God’s sovereignty; for John Wesley it was Romans 6–8 and entire sanctification; for Karl Barth it was Romans 1–2 and God’s righteousness;6 for David Watson it was Romans 6 and being dead to sin.

We may confidently say at the outset of this study is that Romans is foundational.

All this simply goes to show that this letter to the Romans cannot be lightly handled or easily claimed by any one tradition or interpretation. What we may confidently say at the outset of this study is that Romans is foundational.

Romans lays foundations

Martin Luther, whose encounter with Romans led to a personal revival and the subsequent European Reformation, wrote in the preface to his commentary on the letter:

This Epistle is really the chief part of the New Testament and the very purest gospel, and is worthy not only that every Christian should know it word for word, by heart, but occupy himself with it every day as the daily bread of the soul. It can never be read or pondered too much, and the more it is dealt with, the more precious it becomes and the better it tastes.7

Few other epistles come close to covering the breadth and depth of ground that Romans does.

Romans is the first epistle in the New Testament and, as mentioned earlier, the longest. It is arguably the most important and most influential. Few other epistles come close to covering the breadth and depth of ground that Romans does. While the majority of Paul’s letters may go into greater length on certain issues like Christ’s divine nature, church life, eschatology, circumcision, no other epistle has the scope and depth, touching on most major themes in theology and church life: from God’s revelation, to creation, to salvation, to sanctification, to mission, to church relations, to spiritual gifts, politics, and ethics.

My great friend Mark is a warrior who distinguished himself over twenty-three years of military service, including seventeen in the famed SAS. While in a semi-drunk state, following a two-week drinking binge celebrating his success and survival in the First Gulf War, he was convicted of sin and converted to Christ while randomly flicking through TV channels in his room. He had paused to listen to a TV evangelist, who was staring as through the screen, and, in a Spirit-inspired moment, described Mark’s life, failures, and successes and need for Christ who alone satisfies and saves. Mark followed the evangelist’s prayer of commitment. He wept over his sins for an hour, fell asleep, and woke up sober and saved.

Mark knew next to nothing about the faith, but was determined to live all for Christ. The first day back at Hereford Camp he incurred ridicule from his SAS colleagues as he bowed his head and said grace in the food hall. Jeers, derision, and amazement followed – he told me it was one of the toughest things he ever did, up there with Special Forces selection! Immediately his womanizing, drinking, fighting, and swearing ceased. He was perhaps the only declared Christian out of the 250 soldiers serving in the SAS, and he walked a lonely road for many years.

Shortly after his conversion, he was posted to help run the infamous Belize Jungle warfare training school for six months as its chief instructor. Given the unusual nature of his career, which he believed God told him to stick with, he was unable to attend church regularly or be discipled in the regular manner. Special Forces require special discipling. But he was an avid reader, and just as he was about to take his jungle posting, he walked into a bookshop and spotted a fourteen-volume set of books called Romans. As a soldier, he was interested in military history, and he assumed they were a comprehensive account of the rise and fall of the Roman empire. Of course it turned out that this was no military history, but the whole collection of over 350 sermons on Romans by Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones. For the next six months in Belize’s swamps and jungles, while being devoured by leeches, Mark himself devoured all fourteen volumes of Lloyd-Jones’s series. When he was subsequently posted to Bosnia’s nightmare, Mark often had a volume of Romans tucked in his Bergen rucksack. God trained him, discipled him, and theologically educated him as he studied Romans. Not knowing how to preach but sensing he should share his faith, Mark would visit prisons and simply read aloud the latest Lloyd-Jones sermon to engage his listeners. He began to see people come to faith in Christ, and even saw healings occur as he prayed for others. There were also miracles of divine deliverance and providence in his own life. Isaiah 54:13 prophesies that one day “all your children will be taught by the Lord”, and indeed, in twenty-five years of ministry, I have seldom met anyone like Mark – someone who has been taught by God, taught through Romans.

When he said it was about the Bible, she mocked him for reading this “God-stuff”. He replied that if she didn’t shut up, he’d throw her into the water and feed her to the sharks.

Mark recalls that he was reading a Lloyd-Jones volume as a new believer on a boat trip, having some R&R, when a fellow soldier’s wife asked what he was reading. When he said it was about the Bible, she mocked him for reading this “God-stuff”. He replied that if she didn’t shut up, he’d throw her into the water and feed her to the sharks. Noting he was an SAS instructor, the mocking ceased. Mark later admitted it was not the best witness, but he was a new Christian, and as he says: “I hadn’t yet got to Lloyd-Jones on holiness in Romans 6–7.” God had remarkably discipled Mark through his study of Romans; it was the best possible discipleship course and theological education this warrior could have received, and he emerged – not from the desert but from the jungle – a man of God.

Few reading this book will go to theological college for sustained study of theology. And such academic study is certainly no guarantee you will know any more about God or look any more like God. But I can guarantee this: if you master Paul’s epistle to the Romans, and if its truths master you; if you pray and study and apply your way through it; then you will not only know more biblical theology than most ministers of religion, you will bear more fruit, such that you can freely sing with the psalmist, “I have more understanding than all my teachers” (Psalm 119:99).

Why not, on your own or with a small group of friends or family, read the whole book in one sitting, aloud, and try to summarize in one sentence what stands out to you as its central subject?

Notes

1. Chapter 16 implies at least five house-holds, house-churches – one that meets in Priscilla and Aquila’s house (verse 5) another meeting in Aristobulus’s house (verse 10) in Narcissus’ house (verse 11) at Asyncritus’ (verse 14) and at Philologus’ (verse 15).

2. F. F. Bruce, The Epistle of Paul to the Romans: An Introduction and Commentary, Tyndale New Testament Commentaries, InterVarsity Press, 1983, p. 11f, italics mine.

3. Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Volume 1, 1910, p. 766, quoted in J. Dunn, “Romans” in G. F. Hawthorne, R. P. Martin and D. G. Reid (eds.), Dictionary of Paul and His Epistles, InterVarsity Press, 1993, edited by

4. Quoted in Dunn, “Romans”, p. 839.

5. C. K. Barrett, The Epistle to the Romans, Black’s New Testament Commentary Series, Second Edition, A & C Black, 1962, p. 27.

6. Noted by Charles D. Myer’s “Romans”, in Anchor Bible Dictionary, Volume 5, Doubleday, 1994, p. 816f.

7. Martin Luther, Commentary on Romans, Kregel Classic, Zondervan, trans. J. Theodore Mueller, 1954, p. xiii.