James Mumford takes a look at the true story of a man who pioneered translating the bible into English; William Tyndale.

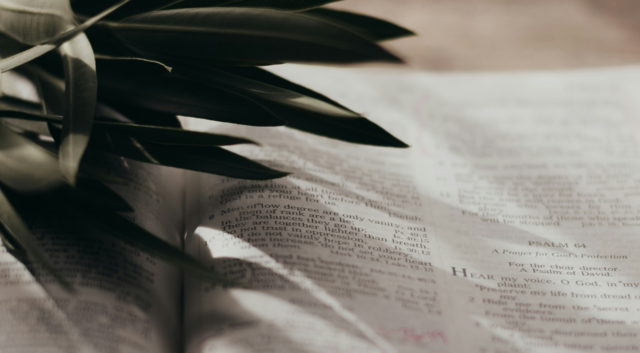

I do marvel greatly, dearly beloved in Christ, that ever any man should repugn or speak against the scripture to be had in every language. For I thought that no man had been so blind to ask why light should be showed to them that walk in darkness.

Seeing that it hath pleased God to send unto our Englishmen the scripture in their mother tongue, considering that there be in every place false teachers and blind leaders; that ye should be deceived of no man, I supposed it very necessary to prepare this Pathway into the scripture for you, that ye might walk surely, and ever know the true from the false.

It’s almost impossible to imagine a time when you weren’t allowed to read the bible for yourself. Today, Old and New Testaments have been translated into every language under the sun. There are Gideon bibles at every hospital and every hotel room in Britain. Copies of scripture are preserved in millions of churches, schools and homes around the world. But five hundred years ago it was a different story. In the Tudor England of Henry VIII, the only text available was in Latin, which only priests and scholars could read. And that Latin translation was itself out of date, the same edition having been in use for over 1200 years.

Many priests, commissioned to teach the people God’s word, could not even read it themselves.

This was the frustration that faced a young student in 1512. When William Tyndale left home to study in Oxford he was appalled by the ‘secret’ status of scripture. The fact that his native countrymen in the Vale of Berkeley, farmers, shepherds and cloth-workers of the Cotswolds were barred from reading in their own language a bible locked up in ivory towers, infuriated the young man. He protested, “In the universities they have ordained that no man shall look in the Scripture until he (has studied) eight or nine years.” He also attacked the explanation given by the elite, “They bark and say, “the scripture maketh heretics!” and “it is not possible for them to understand it in the English,” because they themselves do not in Latin.” Many priests, commissioned to teach the people God’s word, could not even read it themselves. However, learning the original language of the New Testament and going back to the actual letters the apostle Paul wrote, came as a breath of fresh air to the stifled Tyndale. And he longed for others to breathe the same air. A contemporary historian records that it was on account of his “lamenting” the “ignorant state of his native country” that his vocation was decided. Disputing with a prominent clergyman who hated the very idea of translating the bible into English, Tyndale declared, “If God spare my life ere many years, I will cause a boy that driveth the plow to know more of the Scriptures than thou dost.”

No vernacular translations of the bible had been, or were likely to be, authorised by the crown or by the church

There was only one problem with Tyndale’s developing ambition. It was illegal. No vernacular translations of the bible had been, or were likely to be, authorized by the crown or by the church. Therefore, after years of learning the necessary skills in Oxford and possibly Cambridge, and after working as a clergyman in London, in April 1524 William Tyndale set out for Germany. It was no coincidence that Cologne and then Worms became the sites of his historic achievements. Ever since 1517, when an indignant monk called Martin Luther had sent Shockwaves through all of Europe by nailing to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenburg ninety-five theses – protesting against the corruption of the church and appealing for its reform – Germany had become the centre of various Reformations which ignited and divided 16th century Christendom. The Reformers said that Christians must return to their roots. To figure out what we really should believe and practise as followers of Jesus, we must go back to the bible. This conviction was so controversial because it involved a reaction against the contemporary understanding of the Church’s tradition as a separate, distinct source of revelation in addition to Scripture.

The ugliest part of that tradition was its justification of ‘indulgences’. This practice allowed you to purchase special papal decrees which claimed to ensure the release of dead relatives from purgatory or even your own forgiveness from sin. Yet this flew in the face of the bible’s teaching. So Scriptura sola, ‘by Scripture alone’, became one of the great slogans of the Reformation. And Luther, declaring that “a simple layman armed with Scripture is to be believed above (an indulgence-decreeing) council without it”, successfully translated the bible into the vernacular of his own peasant people. It was in Germany that Tyndale’s personal project became part of the wider Reformation.

he became the first man to translate anything directly from Hebrew into English.

Despite Luther’s influence, however, Tyndale had no English model for what he wanted to do in the 1520s. The New Testament had never before been translated from Greek into English. When he began translating Old Testament manuscripts in the 1530s, he became the first man to translate anything directly from Hebrew into English. His most recent biographer, David Daniel, wrote, “he is a pioneer.” But the success of his immense task not only depended upon his linguistic skill (he was fluent in eight languages) but also upon his understanding of everyday English. Daniel also says of Tyndale: “part of his genius as a translator was his gift for knowing how ordinary used language at slightly heightened moments, and translating at that level (phrases such as) ‘Am I my brother’s keeper?’, ‘the burden and heat of the day’, ‘the signs of the times’, ‘a law unto themselves’.” If God had intended the scriptures to be originally written in the language of the people, and to be widely read by the people, Tyndale reasoned that they must be rendered into the appropriate dialect. And marks of his success are many; it is estimated that Tyndale’s translation has been read by ten thousand times as many people as Chaucer, forming the basis for the King James Bible in 1611 and the Geneva Bible used by the Pilgrim Fathers.

The New Testament translation was completed in 1525…and smuggled into England

Tyndale was appalled, however, by the reception of his work at home. The New Testament translation was completed in 1525, printed at Worms and smuggled into England, wrapped in bales of wood, cloth or sacks of flour. It was one thing for the English authorities to burn publicly Luther’s ‘heretical’ tracts. But the fact that of 18,000 copies of his own Worms bible, only two survived, shocked Tyndale terribly. He never recovered from Cardinal Wolsey’s consistently cynical campaign to deprive the people or destroy the Scripture. He was shaken “that ever any man should repugn or speak against the scripture to be had in every language.” He was devastated by the clerical and academic opposition to his life-long project “to prepare a pathway into” it for all people, whether prince or ploughman.

The most gruesome of deaths was ensured

And it wasn’t only his books that were burnt. In 1535, while he was living in Antwerp, carefully making revisions to a fresh edition of his New Testament, and industriously ploughing through the remaining books of the Old Testament, Tyndale was betrayed by a man he had befriended. Henry Phillips, a disgraced nobleman’s son, was paid by an unknown but influential English clergyman and/or statesman to carry out a secret operation. Having been welcomed into his household, Phillips then handed Tyndale over to officers from the Court of Brussels. With loyal English merchants unable to help him, and far from his supporters in England, Tyndale was at the mercy of a monarchy fearful of and hostile to the Reformation. And across the channel, the establishment was overjoyed, having caught what they considered the biggest heretical fish, proof at least of the extent of Tyndale’s influence and the importance of his work. After over a year of cold imprisonment, Tyndale was condemned as a heretic, degraded from the priesthood and, as Foxe’s book of Martyrs informs us, “tied to the stake, and then strangled first by the hangman, and afterwards with fire consumed, in the morning at the town of Vilvorde.” The most gruesome of deaths was ensured for a man who had plotted no rebellion, committed no crime, written no slander, but had simply believed in the Bible.